Arriving at Angel Island State Park, visitors are greeted by sweeping views of the Bay, salty air, and the warmth of the sun and the sound of distant waves. The beauty is immediate, but just beneath the surface lies one of the most complex and powerful histories in California's state park system. Angel Island is more than a destination — it is a place where personal, national, and cultural histories converge.

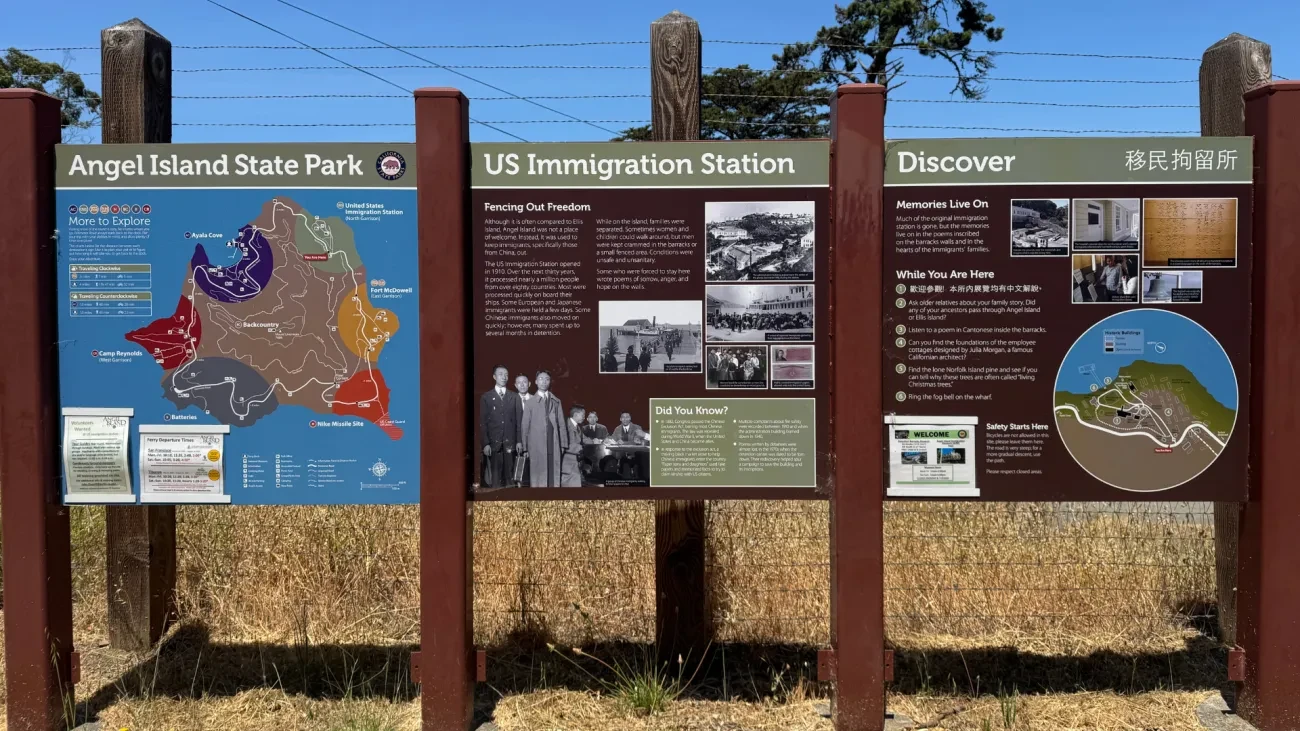

Many begin their visit on the Northridge Trail, a shaded path that climbs from the Ayala Cove ferry dock before connecting with the Perimeter Road. This paved route hugs the hillside, offering views of the Bay and the hills surrounding Tiburon. Around a mile in, a turnoff leads through a quiet gate and into a place that invites deeper reflection: the Angel Island Immigration Station.

The History Behind Angel Island State Park

From 1910 to 1940, this station served as the primary immigration processing and detention center on the West Coast. Historians estimate that approximately 300,000 immigrants were processed at Angel Island during its 30 years of operation. While it is often compared to Ellis Island, Angel Island operated very differently. It was built not to welcome newcomers, but to interrogate, detain, and often exclude them, especially under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first U.S. immigration law to target an entire ethnic group.

Immigrants were subjected to invasive medical inspections, intense interrogations, and lengthy detentions. Non-Chinese immigrants were typically held for two to three days, while Chinese immigrants often stayed two to three weeks — and some for several months or even years. Many were ultimately denied entry. Roughly one-third of those processed were Chinese, one-third from Japan, and one-third arrived from India, the Philippines, Russia, Korea, and over 75 other countries.

Stories Etched in Wood

Today, the detention barracks remain. Restored and preserved, they house exhibits that tell this difficult history. Perhaps most striking are the poems etched into the wooden walls by detainees. These verses capture grief, resilience, and hope — a powerful testament to the human spirit within an inhumane system. Many of the poems describe longing, injustice, and separation. Some express despair; others push back against the unfair treatment they endured. These writings turn the building into more than just a detention site — they transform it into a living archive, a rare place where those once silenced carved their voices into permanence.

Interpreting these stories is delicate, emotional work. “Establishing trust is essential when providing a tour at the detention barracks,” says Cynthia Pu, a state park interpreter. “What are the visitors’ family immigration history? What is their relationship or conflict with the American identity?” She adds, “The history of the immigration site is intrinsically sensitive and very human. Asking visitors to place their trust in us to provide a space that is safe for the possibility of painful conversation is a massive ask. Also, asking the tour guides to place themselves in vulnerability while they’re delivering not just information, but human stories is an ask with equal weight.”

In 1966, an official report recommended that the Immigration Station buildings be removed due to their deteriorated condition, and in 1967 it was submitted to California State Parks in preparation for the 1969–1970 fiscal year. When Ranger Alexander Weiss began working on the island in 1970, he found Chinese poetry carved into the walls of the detention barracks. Despite being directed to prepare the site for demolition, Weiss resisted, and his actions helped spark a broader movement. Students, descendants, and Asian American community leaders — including early activist Chris Chow — organized to preserve the site and push back against the state’s plans. In a detailed firsthand account, Chow describes how community members challenged the official narrative and demanded that these voices be protected. Their advocacy reminds us that California’s state parks belong to the people — and that collective action can drive lasting change. Their efforts led to the founding of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF) and to ongoing projects like Immigrant Voices, which continue to connect past and present.

Layers of History: Beyond Immigration

Angel Island’s layered history goes back much further. Long before it became a site of federal oversight, it was home to the Coast Miwok people, whose descendants are now part of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the island was used as a cattle ranch, a quarantine station, and a military post through several wars. Together, these layers reflect the evolving and intersecting histories that have shaped California.

Today, Angel Island offers opportunities not only for remembrance, but also for recreation. After visiting the Immigration Station, many continue along the Perimeter Road, a five-mile paved loop ideal for walking or biking. For a more strenuous option, the Mount Livermore summit trail rewards hikers with panoramic views. Picnic areas, restored military buildings, and interpretive signage dot the island, encouraging both exploration and education.

Pu approaches interpretation with empathy. “The history must be told with empathy,” she says. “That empathy could have as many facets as trying to connect with a fourth grader who is just excited to be on island for the first time, trying to build a bridge with a visitor who has decried ‘illegal immigration,’ and trying to encourage a college student who feels frustrated and helpless with current events.” Her approach is grounded in three tenets: “One, studying the history closely to be faithful with what historians have uncovered. Two, adjusting the language to be impactful with any audience, from excited kindergarteners to apprehensive adults. Three, constantly evaluating how my tour can be both frank and empathetic.”

Plan Your Visit

Getting to Angel Island is part of the experience. Ferries run from San Francisco and Tiburon, with options for private boats or even kayaks for the adventurous. Bicycles are allowed, and a seasonal tram offers a more accessible way to see the island. Campgrounds are also available with reservations. For tips on how to get there, what to do, and how to plan your day, visit this helpful guide from California State Parks.

The short ferry ride — just long enough to feel like a crossing — helps set the tone. As the boat pulls away from the city and toward the island, the noise fades. The water widens. Visitors step onto the dock at Ayala Cove and often pause, taking in the stillness of the landscape and the weight of history. Here, nature and memory coexist.

Today, school groups regularly visit the Immigration Station as part of California history and social studies curricula. Students walk through the very rooms where detainees waited and wrote. For many, it’s a first encounter with immigration history told through a West Coast lens — a moment that challenges assumptions and adds depth to their understanding of America’s past. In-person tours and free virtual tours, plus classroom resources, are available through AIISF’s field trip page.

“If someone did something as simple as hike, enjoy the sights, and have a fun day — carry that love of parks with you,” Pu says. “Seek out other state parks and support increasing the access of recreation and outdoor space in our public lands.” But for those who visit Angel Island’s historic sites — the Immigration Station, military installations, or former Coast Miwok villages — she hopes they carry something deeper: “The memory of the human stories there, and the understanding that history is never just history. All time is interconnected, and echoes of the past can always be seen and inform the present.”

Why Angel Island State Park Matters Today

The Angel Island Immigration Station operated during a time of widespread anti-Asian sentiment in U.S. policy. In addition to the Chinese Exclusion Act, laws like the Immigration Act of 1917 and the National Origins Act of 1924 imposed quotas and barred immigrants from entire regions. Angel Island became a physical embodiment of those policies. Understanding what happened here means understanding how immigration policy has long reflected — and shaped — American identity, inclusion, and exclusion.

The island invites visitors to pause, observe, and engage with its stories — some well-known, others still emerging.

Recent efforts to sanitize public memory, including a new initiative at national parks encouraging visitors to report exhibits that portray American history "negatively," only underscore why Angel Island matters. The poems carved into the detention barracks weren’t meant to comfort; they were meant to endure. And they did — despite attempts to demolish the buildings that held them. Angel Island reminds us that historical truth is often uncomfortable, but essential. If we lose our ability to confront the hard parts of our past, we lose the chance to learn from them. At a time when immigration remains a subject of ongoing national conversation, Angel Island serves as a mirror. The policies and prejudices of the past echo in the present: suspicion of newcomers, long detentions, and family separations persist in new forms. While immigration policy has evolved, the human impact of detention, exclusion, and uncertainty remains deeply felt.

Places like Angel Island don’t just preserve history — they challenge us to confront it. They ask who we include in our narratives, who we exclude, and how we can do better. Even within systems built to silence, people have always found ways to speak.

Whether drawn by the scenery, the stories, or the questions it raises, Angel Island State Park is a place that leaves an impression. It doesn't just ask visitors to look — it asks them to see. And perhaps, to care a little more deeply about the people and histories that shape our shared home.